Introduction

Stamps provide a unique perspective on how nations see themselves and, more importantly perhaps, how they may wish to be seen. Since the introduction of the world’s first adhesive postage stamp, the Penny Black, in 1840 their primary purpose has been to show that postage fees have been paid but they also act as miniature ambassadors, tiny paper representatives of a nation’s character and culture. When in 1922 an Irish Free State emerged as a self-governing dominion within the British Empire it represented for many Irish people, at home and abroad, the realisation, albeit imperfectly perhaps, of a long-cherished aspiration and it was natural that the new Government sought, as soon as possible, to replace contemporary British stamps with new Irish ones. In 1922-23 new stamps would appear and this centenary provides an opportunity to think a little about the broader cultural role of Irish stamps in representing the evolving nature of Irish identity since the stamps of King George V were first overprinted in Irish a century ago.

Stamps provide a unique perspective on how nations see themselves and, more importantly perhaps, how they may wish to be seen. Since the introduction of the world’s first adhesive postage stamp, the Penny Black, in 1840 their primary purpose has been to show that postage fees have been paid but they also act as miniature ambassadors, tiny paper representatives of a nation’s character and culture. When in 1922 an Irish Free State emerged as a self-governing dominion within the British Empire it represented for many Irish people, at home and abroad, the realisation, albeit imperfectly perhaps, of a long-cherished aspiration and it was natural that the new Government sought, as soon as possible, to replace contemporary British stamps with new Irish ones. In 1922-23 new stamps would appear and this centenary provides an opportunity to think a little about the broader cultural role of Irish stamps in representing the evolving nature of Irish identity since the stamps of King George V were first overprinted in Irish a century ago.

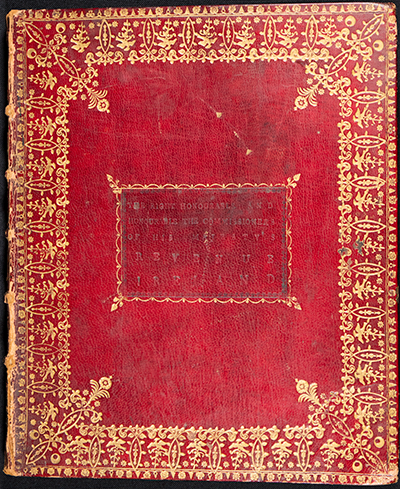

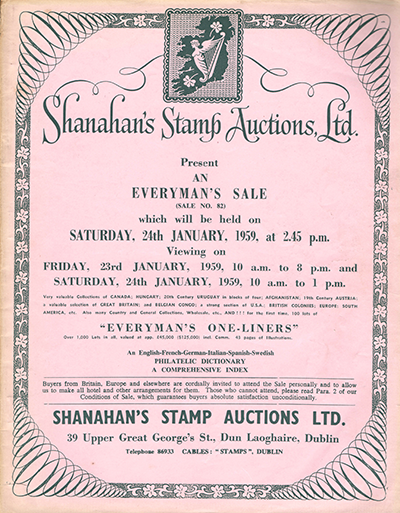

There was Irish involvement in the development of postage stamps from the start: the Clare-born artist, William Mulready, produced a decorative pre-paid envelope in 1840 but his style was altogether too allegorical for public taste and his stationery was so widely caricatured that it had to be withdrawn by the Post Office. An emigrant Irish engraver, Robert Clayton, designed one of the first New South Wales stamps and another Irishman, Henry Archer, invented a perforating machine which facilitated separation of stamps. Ireland is also sometimes accorded the honour of having the world’s first stamp album, a unique collection of Irish revenue stamps put together in 1774 in a beautiful morocco-bound book by John Bourke, Receiver General of Stamp Duties in Ireland, and now in the library of the Royal Irish Academy. One of the finest early stamp collections was made by Gerald Fitzgerald, 5th Duke of Leinster who bequeathed it to the Dublin Museum of Science and Art, now Ireland’s National Museum. Less altruistic were the activities of Paul Singer, the Bratislava-born businessman, whose stamp auctions briefly made Dublin a centre of international philatelic importance until his stamp empire, a pyramid scheme built on a constant influx of new money, collapsed in 1959.

There was Irish involvement in the development of postage stamps from the start: the Clare-born artist, William Mulready, produced a decorative pre-paid envelope in 1840 but his style was altogether too allegorical for public taste and his stationery was so widely caricatured that it had to be withdrawn by the Post Office. An emigrant Irish engraver, Robert Clayton, designed one of the first New South Wales stamps and another Irishman, Henry Archer, invented a perforating machine which facilitated separation of stamps. Ireland is also sometimes accorded the honour of having the world’s first stamp album, a unique collection of Irish revenue stamps put together in 1774 in a beautiful morocco-bound book by John Bourke, Receiver General of Stamp Duties in Ireland, and now in the library of the Royal Irish Academy. One of the finest early stamp collections was made by Gerald Fitzgerald, 5th Duke of Leinster who bequeathed it to the Dublin Museum of Science and Art, now Ireland’s National Museum. Less altruistic were the activities of Paul Singer, the Bratislava-born businessman, whose stamp auctions briefly made Dublin a centre of international philatelic importance until his stamp empire, a pyramid scheme built on a constant influx of new money, collapsed in 1959.

Stamp collecting has nothing like the following it had in the days when so many school boys and school girls devoted a few minutes of their lunch-time to “swopping” stamps but the hobby continues to offer much, not just to the philatelist and postal historian, but to anyone interested in aspects of wider social history, graphic design and printing. Each stamp, when you think of it, is the culmination of a process which sifts ideas gathered from the public, adds the expertise of various specialists and draws on diverse creative, technical and artistic talents to produce a little work of art. The transformation of Ireland from the Free State of a century ago, through some years of rather self-absorbed introspection, to today’s more outward-looking and cosmopolitan land has not been straightforward and the complexities of that transition, social and political, will remain the stuff of academic histories. Easier to grasp is the visual record of our postage stamps and the stories that lie behind them for they offer unique insights into the ever-changing identity and aspirations of the Irish people – a remarkable achievement for some little pieces of coloured paper!

Stamp collecting has nothing like the following it had in the days when so many school boys and school girls devoted a few minutes of their lunch-time to “swopping” stamps but the hobby continues to offer much, not just to the philatelist and postal historian, but to anyone interested in aspects of wider social history, graphic design and printing. Each stamp, when you think of it, is the culmination of a process which sifts ideas gathered from the public, adds the expertise of various specialists and draws on diverse creative, technical and artistic talents to produce a little work of art. The transformation of Ireland from the Free State of a century ago, through some years of rather self-absorbed introspection, to today’s more outward-looking and cosmopolitan land has not been straightforward and the complexities of that transition, social and political, will remain the stuff of academic histories. Easier to grasp is the visual record of our postage stamps and the stories that lie behind them for they offer unique insights into the ever-changing identity and aspirations of the Irish people – a remarkable achievement for some little pieces of coloured paper!

Stephen Ferguson

General Post Office Dublin